Building Sustainable Economies

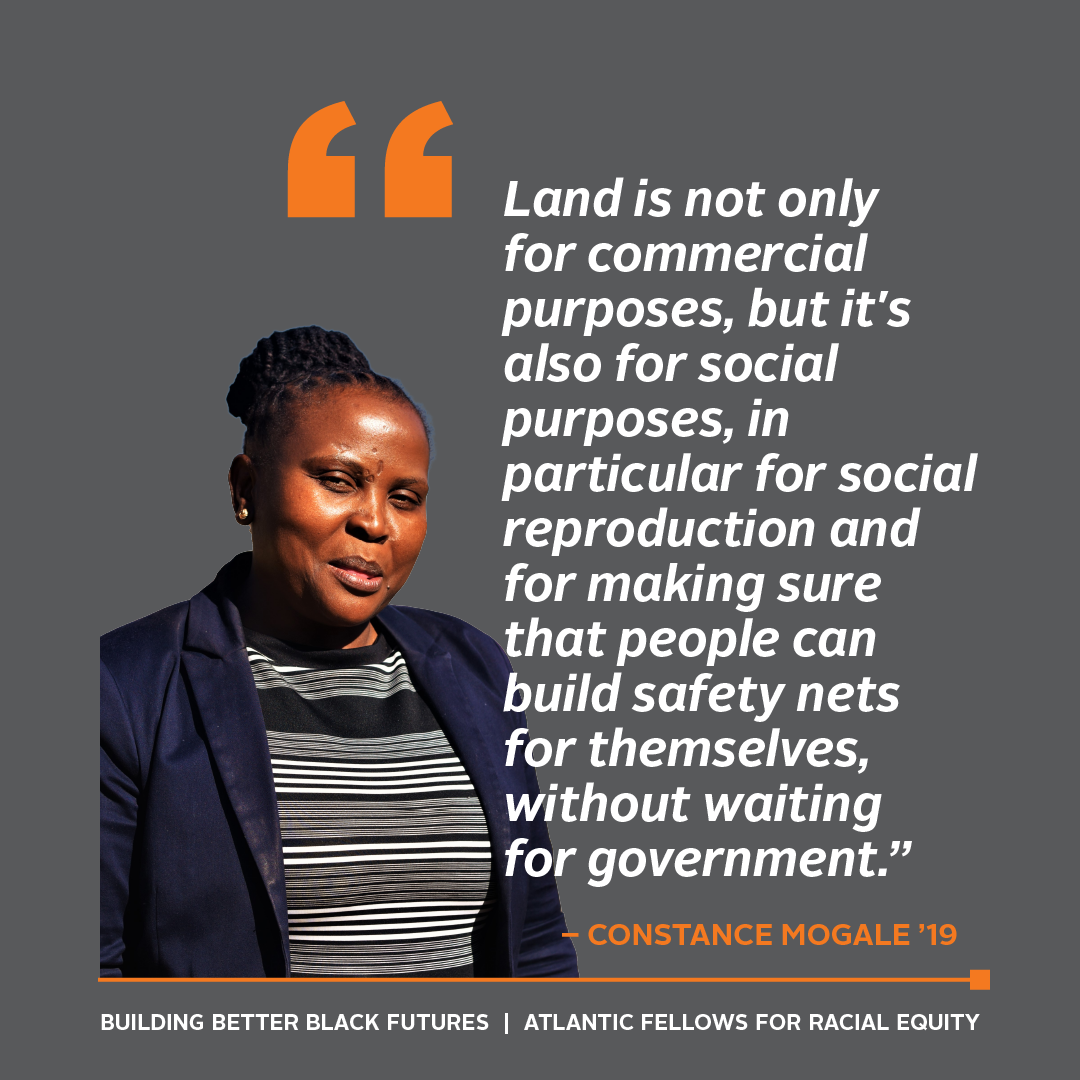

In the early days of the pandemic, when Constance “Connie” Mogale'19 visited the rural communities in Mpumalanga with whom she organises for land rights, she was inspired by what she encountered: people, primarily women, were living off vegetables and fruit trees grown in their backyards and were sharing with others near and far through their communal networks of care.

In sharp contrast with the desperation in urban areas like Gauteng, her rural communities had fared relatively well, pandemic-related restrictions notwithstanding. Their self-sustenance reinvigorated her commitment to the critical place of land ownership in cultivating and deepening a community’s socio-economic health. “We could see that the resilience was there because of that piece of land,” she says.

Land remains a hotly contested issue in South Africa. Despite decades of activism and a subsection of the 1994 Constitution expressly focused on redistribution, 72 percent of land in South Africa remains in control of white people who make up 7.7 percent of the population.

“The situation in South Africa is at this dire stage because of the structural factors that we inherited from the apartheid government,” Connie says. “We are the majority constituency; we have the will power amongst the people, but Government never had political will to redistribute land along racial lines.”

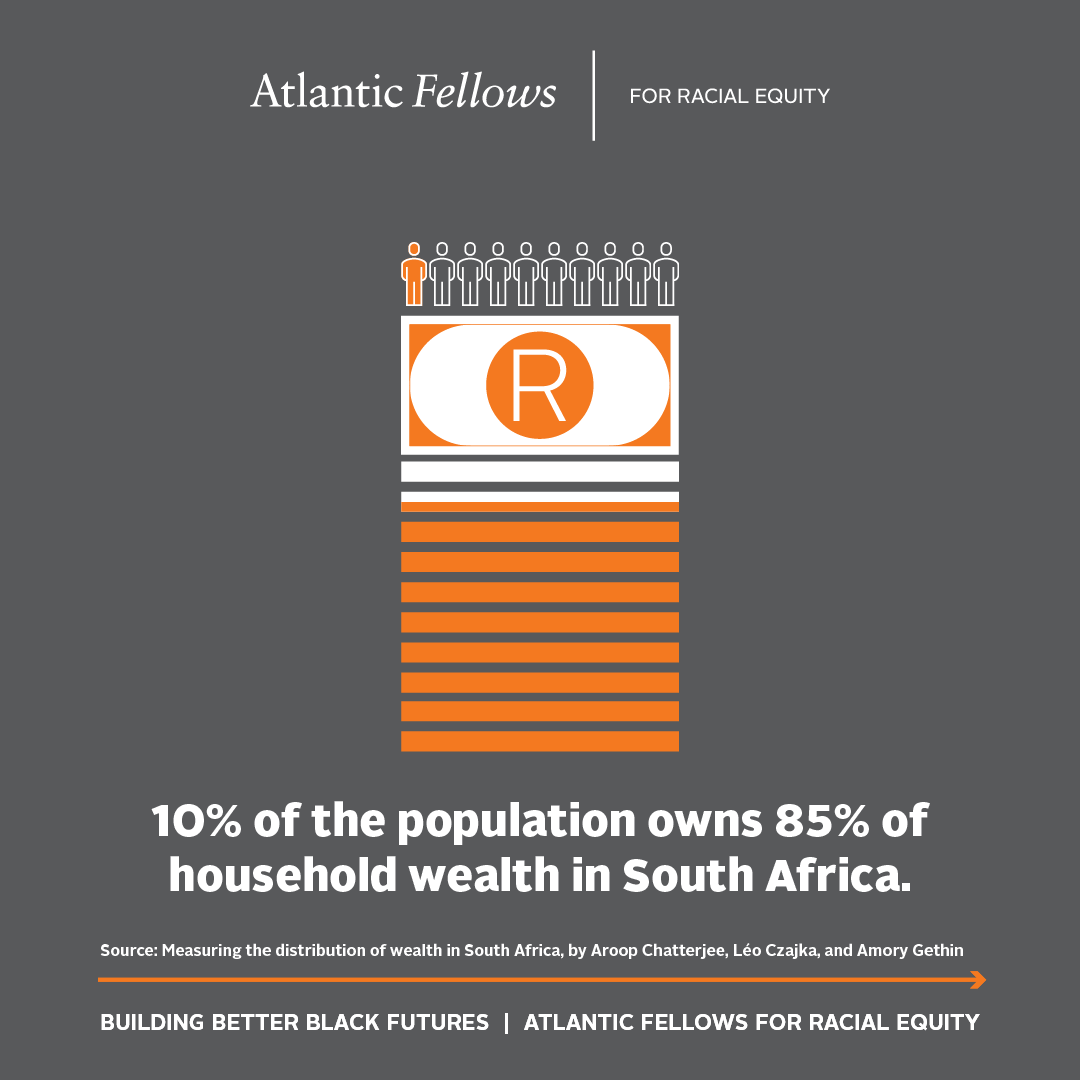

This inequality echoes broader economic trends in the country. South Africa is infamous for being the world's most unequal country with an alarming 70 percent youth unemployment rate. And at a time when food prices continue to threaten the world’s poorest counties, such stark inequality has huge implications for the South Africa’s future.

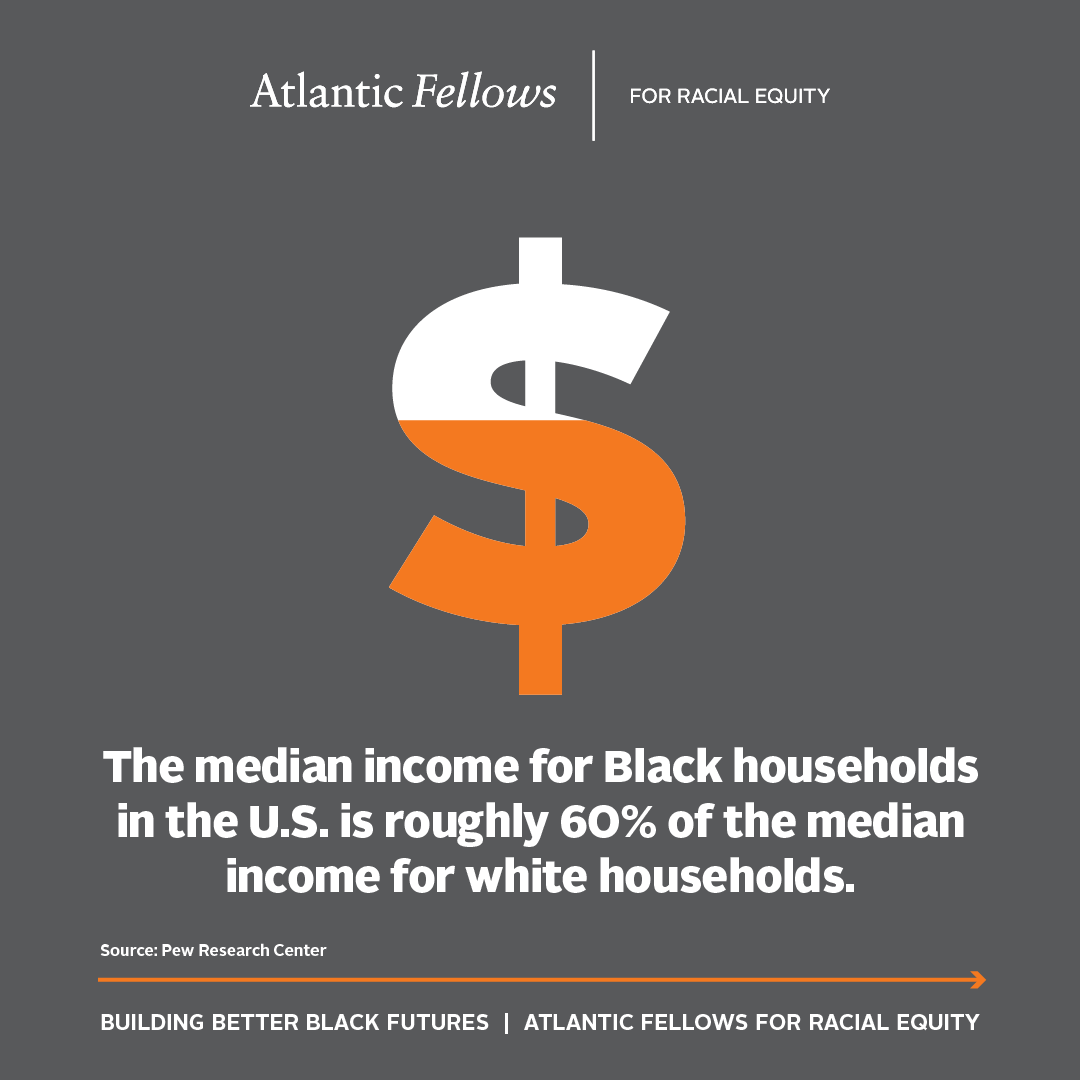

The United States is also marked by economic inequity along racial lines, rooted in histories of discrimination and exploitation, including redlining, employment discrimination, and systematic under-resourcing of public infrastructure. In addition, contemporary realities of low wage work, mass incarceration and continued discrimination, particularly against poor people of colour, exacerbate the situation.

For Connie, this moment requires redistributive policies that are sensitive to the overlapping impacts of gender, class, and race are a crucial part of the solution. She observes that women in low-income families bear an outsized burden of care for the young and the elderly, including the youth facing unemployment.

An effective policy would recognise women's contributions to the economy through their existing unpaid work, a cornerstone of healthy communities–indeed the health of the country–and provide them with financial relief and other social supports. Advocates also call for the national government to implement a permanent basic income grant like the social relief grants that were put in place as a salve to the pandemic. And Connie believes the government must follow through on land redistribution, not only for economic emancipation and income generation but also to support the kind of community safety-net that she witnessed in Mpumalanga in those early days of the pandemic. That kind of land, central to communities’ health will increase the effectiveness of other social programmes in response to disasters like the pandemic.

At the heart of these proposals is the idea of identifying and supporting communities’ existing expressions of resilience and self-sustenance. Connie believes this approach is crucial for sustained, long-term change. Such an approach could also benefit the U.S.

Learn more:

Land Accountability and Research Centre at University of Cape Town; Calls for a Basic Income Grant

Lead image originally published in The Conversation.

This piece is part of our 2022 Policy Slate for Racially Equitable Futures. Click here to visit the summary page and explore other issues.