A Path to Reparations

As we observed last year, the paths to actualising reparations for communities of colour across the world are likely to be highly contextual, given the highly contextual histories of harm that different communities have experienced. This approach animates a historic reparations programme in Evanston, Illinois.

Launched in April 2021, Evanston’s Restorative Housing Program allows Black residents whose ancestors were denied housing loans because of racial bias to apply for a $25,000 payment to cover their current housing needs, such as home repairs and property costs. It's a notable development in the broader context of a United States, where financial reparations for Black Americans have long been viewed as politically unviable.

While many have celebrated the programme, it is not without its critics. They question whether a grant programme, rather than direct cash payments, can be viewed as reparations. Indeed, conversations about reparations in the United States tend to emphasize direct cash payments, particularly from the federal government, for the harms of enslavement–among them centuries of forced and unpaid labour of enslaved people that fuelled the U.S. economy and made the country wealthy.

In their 2021 book, From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century, Duke University professors observe that the U.S. federal government has had several opportunities to redress these harms since enslaved people were emancipated in 1863, but has repeatedly failed to take decisive action.

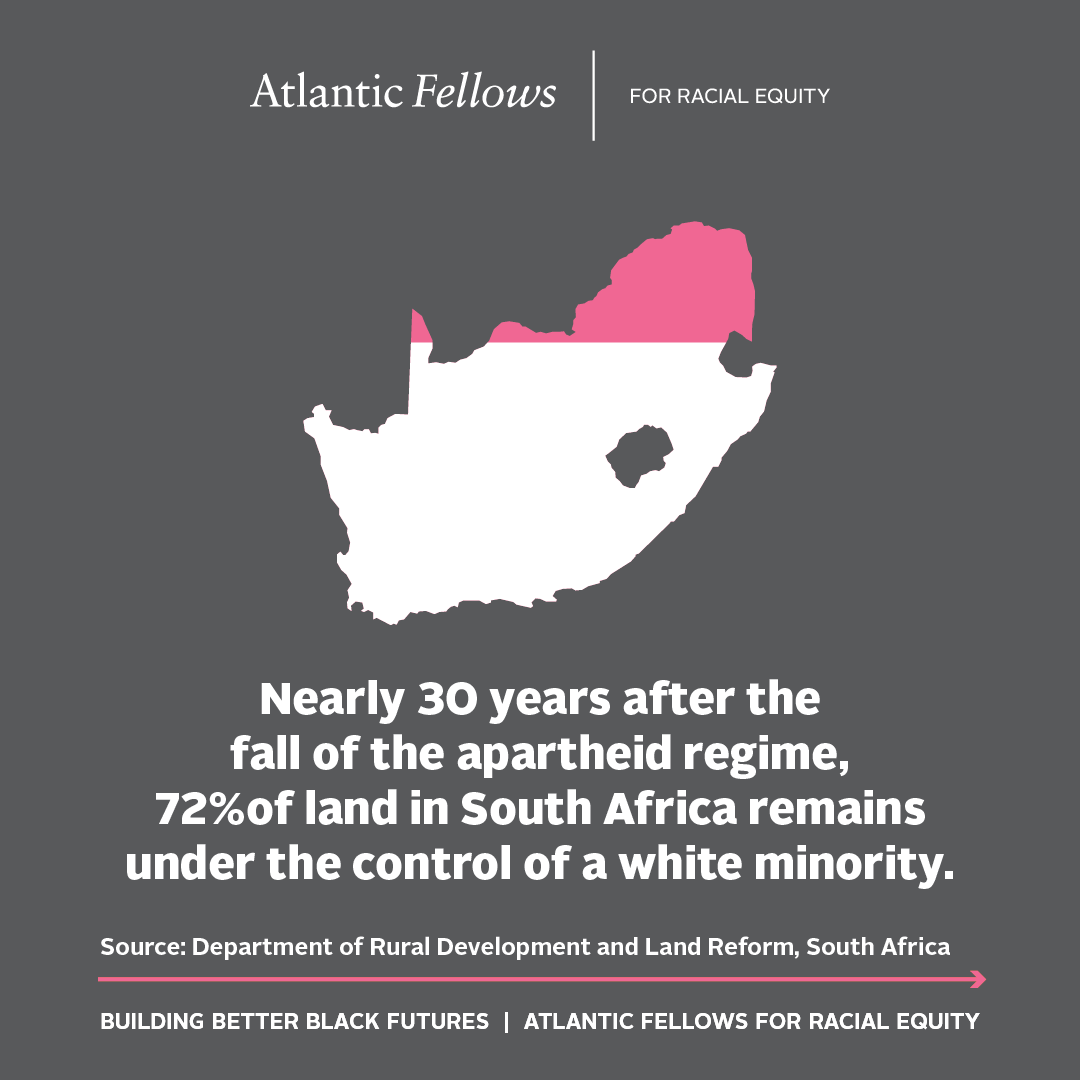

In South Africa, the lack of comprehensive reparations policies for people impacted by apartheid-era political violence also persists, despite the recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation process issued two decades ago. As Constance "Connie" Mogale'19 observes, land remains concentrated in the control of a small white minority of the population.

Across both countries, a lack of political will to address reparations squarely reverberates as a hindrance to achieving more just futures. Like other concerns raised throughout our 2022 Policy Slate for Building Better Black Futures, strengthening democratic accountability to communities of colour is a crucial piece of the puzzle for advancing reparations in the U.S. and South Africa.

Critical narrative work can also help shift the political landscape around reparations. Roseline Armange, PhD, a Martinican psychologist and researcher on reparations policies in the Caribbean, offers insight about how to frame and drive reparations policy. As she notes on our podcast Race Beyond Borders, the heart of reparations is a concerted engagement with histories of harm and various modes of repair.

"We can frame reparations so that it goes beyond monetary terms because there [are] different ways of repairing history,” she says. “Doing academic work, artwork, being engaged in anticolonial activities that [move the world] toward more equality [could all qualify as reparations]. For me it has been about psychological ways of repairing myself.”

Within this expansive frame, the reparations programme from Evanston, Illinois, and direct cash payments of descendants of enslaved people in the U.S. both hold sway. Moreover, it becomes clear that while an urgent responsibility of governmental institutions, reparations programmes are not solely the responsibility of government. Other institutions, including museums, universities, and religious institutions, can take up reparations efforts rooted in honest readings of history and that speak to demands of those impacted by harms and are explicit about redressing harms done.

Learn More:

City of Evanston - Restorative Housing Program; HR40 bill on the floor of the U.S. Congress; National African American Reparations Commission; Dr Roseline Armange on Race Beyond Borders; From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century, by William Darity Jr. and A. Kirsten Mullen [Book]; Brookings Institute: Why We Need Reparations for Black Americans [Policy Brief].

Lead Image by Kevin Mohatt/Reuters

This piece is part of our 2022 Policy Slate for Racially Equitable Futures. Click here to visit the summary page and explore other issues.