Internet for All

Few events have affirmed the essential place of communications technology writ large, and the internet in particular, in modern life like the COVID-19 pandemic. Across the world, Zoom, Google Hangouts, and other tools became essential for knowledge workers; to accessing healthcare; and to education.

Technology is also emerging as central to political life too, both in connecting advocates across campaigns and movements and in shaping public perceptions and discourse.

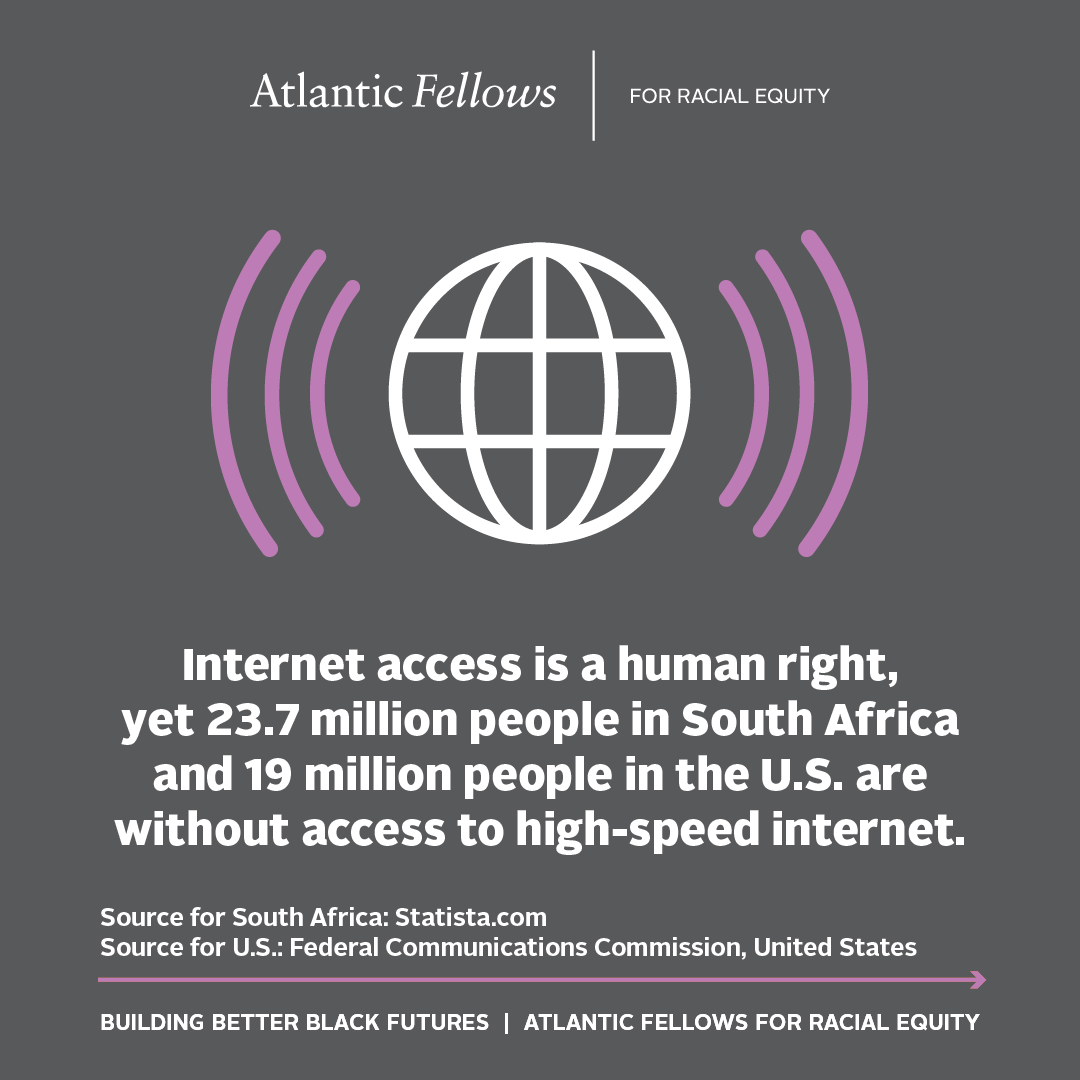

Against this backdrop, inequities in internet access are all the more urgent. Nearly 50 percent of South Africans lack internet access. In the U.S. where access would seem near ubiquitous, 19 million poor and working-class people, and people who live in rural areas find themselves without access to high-speed internet, which is increasingly required for accessing the breadth of benefits possible from internet access.

Last November, South Africa’s Department of Communications and Digital Technologies announced plans to expand the broadband spectrum available to telecommunications firms, a first step toward achieving widespread broadband access by 2023. If successful, these plans could help improve infrastructure, addressing a key challenge to access. Local governments in U.S. communities affected by limited access are also exploring public-private partnerships as potential routes for managing infrastructure costs.

In addition to access, regulation of large tech firms continues to be a major concern around digital technology, and particularly on the ways that social media algorithms are conduits for misinformation and polarisation.

Koketso Moeti’19 observes that misinformation and polarisation are rooted in existing inequities. “What matters [in making sense of the ways technology shape public conversation] is how the prevailing social order shapes technologies and uses them to maintain the status quo and advance the interests of its dominant members,” she says. She argues that effective policy would target the structural injustices that allow bad actors to spread misinformation and manipulate people.

Other advocates call attention to the use of data and artificial intelligence (AI) in decision-making that skews against the wellbeing of communities of colour. This is particularly clear in surveillance and policing practices that rely on algorithms coded with racial bias. A growing coalition of advocates is working, both inside and outside of technology firms, to draw attention to the ethical issues surrounding such uses of data as well as on the design and uses of AI technologies. Among them is the Distributed Artificial Intelligence Research Institute founded by Timnit Gebru, whose earlier work was throttled at Google. Gebru calls for labour protections, including greater union organising power, that would protect staff inside tech companies from the kind of retaliation that she faced.

Importantly, the work of artists, programmers, product managers, and others visioning and building more just futures, are an emerging counterpoint to the market-driven impulses of large tech firms. For these networks and organisations like Afrotectopia, technology can enhance health and wellbeing for vulnerable communities. More support for this work will be important for communities of colour to gain the full benefits that technology offers.

Learn more:

African Digital Rights Network; Race After Technology by Ruha Benjamin [Book]; Afrotectopia; Distributed Artificial Intelligence Research Institute

Lead Image copyright Getty Images/AFP/Sanogo

This piece is part of our 2022 Policy Slate for Racially Equitable Futures. Click here to visit the summary page and explore other issues.